As researchers explore the history of ancient Peru, they find more and more evidence of Pukina: The secret language of the Incas. Pukina (also spelled Puquina ) may very well be the native tongue of the Incas, yet has remained mostly hidden for hundreds of years.

Though Pukina itself is now extinct, much of its vocabulary has extended to the Kallawaya people, a group of traditional healers in the Bolivian Andes. The Kallawaya language is mixed, said to be 14 percent from Quechua , 14 percent from Aymara , 2 percent from Uru-Chipaya , and 70 percent from Pukina, according to researchers, including anthropologist Louisa R. Stark, in her book Machaj-Juyay: secret language of the Callahuayas .

To know the origins of Pukina, it is helpful to also know the origins of the Incas themselves. To begin, most Inca myths point to Lake Titicaca as the birthplace of the Inca—they also name this area the birthplace of the sun and the center of the universe. Before the Inca, a civilization that occupied this famed lake was the Tiwanaku, and the Tiwanaku people spoke Pukina.

In Inca mythology, the founder of the Inca civilization is Manco Capac, who is believed to have been born in the Lake Titicaca area. Or, to put it in mythic terms, to have “emerged from the depths of Lake Titicaca,” near Bolivia’s Isla del Sol. He was, as the legend goes, born in the same region where the Tiwanaku empire stood just centuries prior.

Ethnohistorian of the Andes, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, in her book, The gold mines of the Incas, the Sun and the cultures of the Collasuyu , writes, “The Incas, who believe Lake Titicaca to be the starting point for their myth of origin, argue that the ancestors of their caste, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo [fertility goddess and sister and/or wife of Capac], came from this lake, which allowed them to recover the myth of origin of the Sun and all the prestige of the culture of Tiwanaku, which until then had as main depositary the son of the Sun, owner of [Isla del Sol] and a speaker of Pukina.”

It is also worth mentioning that there are some contrasting ideas about the meaning of the word Titicaca. Titicaca is generally held to be a word from the Quechua language, which is the most widely spoken native language in the Peruvian Andes. In Quechua, Titi , means puma, and caca , means mount. However, if you look at the translation of Titicaca in Pukina , titi means sun and cachi means circle or rim. Which would mean, circle, or rim, of the sun.

Lake Titicaca Tours:

In conclusion, this theory would hold that Pukina can find its origins with the Tiwanaku people of Lake Titicaca; where it was then carried on by the earliest of Incas, as their original language.

As a side note, the Tiwanaku republic collapsed unexpectedly around 1000 AD, with some remnants lingering through 1150 AD. The reason is unclear, but there are different theories relating to drought, intentional destruction due to social issues, and abandonment.

Manco Cápac, the legendary founder of the Inca Civilization.

As the Incas began their migration from the Lake Titicaca to Cusco, they encountered villages along the way whose inhabitants spoke other languages, especially Aymara and Quechua. With time, the Incas adopted these languages as their own, and spoke them frequently.

They continued using Pukina, but over time it became lesser-used as Quechua was already the dominant language of the area. Cusco, founded by Manco Capac in 1200 AD, became the capital of the Inca empire.

Quechua—also referred to as Runa Simi —was the common language, used regularly throughout the villages. However, there are some accounts of another more secretive language used only by the elite—also referred to as Qhapaq Simi . Here are a few such accounts:

By the 16th century the name of this secretive language was not widely known by the common people nor the conquistadors, however, research and colonial records show that it was Pukina.

Sacsaywaman, the Inca stronghold of Cusco

There are barely any historic records of Pukina. Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino, Peruvian linguist, explains that the Spanish had a quite pragmatic approach. So, seeing that the people already spoke Quechua or Aymara, they did not see the use in creating documents in Pukina. “We lost a great opportunity to have materials for this language,” laments Palomino.

What little does exist are fragments of religious texts, one such being a catechism by Alonso de Barcena (1530-1597), Jesuit missionary and linguist. Unfortunately these grammatical and lexical precepts have not been located.

Jeronimo de Ore (1554-1630) also published some pastoral texts in Pukina, from which linguists have been able to further extract grammatical components.

Though not a linguistic text, the fifth viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo , had a declaration that listed Pukina as a general language of colonial Peru.

In more contemporary anthropological works, these statements are reinforced. In Stark’s South American Indian Languages: Retrospect and Prospect, she explains, “During the colonial period the Andean region was characterized by three ‘lenguas generales’—Puquina, Quechua and Aymara.”

It is also worth noting that the native Incas, and many other groups in the Andes, were a cultura agrafas . That is, a culture that does not possess writing. The people of the Andes had more of a spoken culture—though it is worth mentioning that they did use quipus , or talking knots. Quipus are knotted fiber cords used for collecting data and keeping records, and some researchers consider this to be a form of writing.

Quipu in the Museo Machu Picchu, Casa Concha, Cusco. Credit: Pi3.124 (Creative Commons).

Aside from the limited records, there have been other hints that point to the significance of Pukina. In some historical records there are fragments of a small linguistic corpus, different from Aymara and Quechua. While some historians wrote them off as perhaps an offshoot of Quechua, others have taken a closer look.

They found that the idiomatic fragments can not be related to Quechua or Aymara. They belong to a third language, which we now know to be Pukina.

It is also possible to examine the territorial distribution of the language. “This territory can be confirmed to be Pukina thanks to the toponymy,” says Palomino. A toponym is t he general name for any place or geographical entity, and toponymy the study of such names.

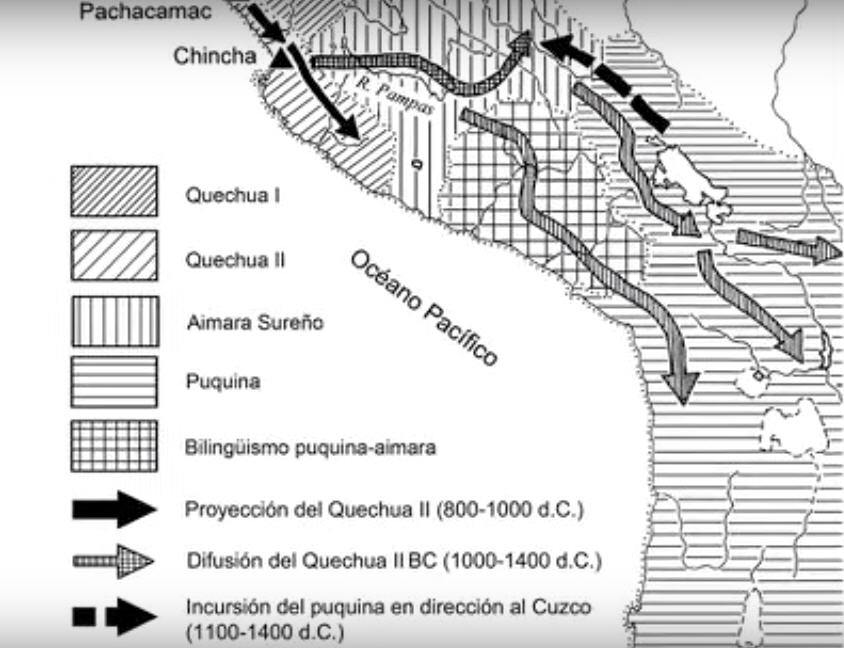

Based on colonial documents, primarily those of Spanish chronicler Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa , we can deduce that, during its time, Pukina spread from Lake Titicaca, continuing Northeast to the Canchis province and throughout the Cusco region, continuing on to the Pacific by way of Arequipa , all to way to Iquique in Chile, northeast to the edge of the Peruvian Amazon , and finally to La Paz and Potosi in Bolivia.

Territorial distribution of Pukina. Source: Palomino

To summarize, here are 5 points that showcase how Pukina has remained a secret for all these years.

Though Pukina is now extinct, Quechua, Aymara, and Kallawaya are still alive and breathing. Here is some statistical information about how these ancient languages have held up after all of this time:

Decoding Pukina is an ongoing task. With every new discovery, we understand more about the ancient Incas and their mysterious language. Contact us to start planning your own Lake Titicaca tour and explore this fascinating cultural region.

Email: [email protected]

Sign up to receive our newsletter for great articles, stunning photos, and special deals.